Interview

Unscripted Lives: Subhashini Ali on Cinema, Struggle, and Silent Labours

Anusha Paul

Published on Aug 18, 2025, 08:12 PM | 11 min read

While you were deeply engaged in political work, wasn't this also the period when you were actively involved in cinema, how was that experience?

When we came to live in Juhu in 1975, we joined a band of cinema enthusiasts—of whom, as I recall, Siddharth Kak was a leading light—and formed a Suburban Film Society that screened world-class films from different parts of India and abroad in theatres across the suburbs. Coincidentally, this was also a time when a space was being created for new kinds of films to be made in Bombay, the centre of the Hindi film industry.

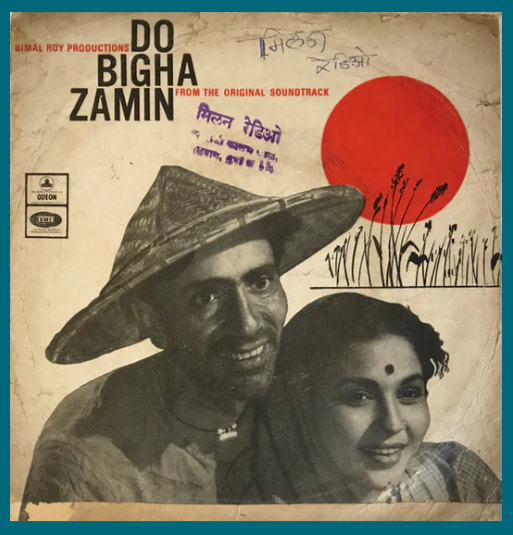

While films like Do Bigha Zameen had been made earlier, they were few and far between, and big commercial films remained the norm. In the late '70s, however, things changed, and a whole slew of more realistic films that dealt with social issues emerged. New directors and new actors were able to access a space in which to develop and taste success.  Image Courtesy: Music Circle

Image Courtesy: Music Circle

It was Shyam Benegal who was the undoubted trendsetter and pathfinder. Already a successful documentary and ad filmmaker, and with the backing of the advertising company Blaze (which had produced much of his earlier work), he burst upon the scene with Ankur and then Nishant. Shyam introduced not only a different kind of Hindi cinema but also a host of young, talented actors and technicians who created both an audience and a large contingent of dedicated, brilliant young people—many trained at FTII—that allowed this movement to flourish.

The National Film Development Corporation (NFDC), headed by cinema lovers Arvind Parekh and Anil Dharkar, also stepped in to provide loans to young filmmakers. It is often forgotten how much government institutions—the much-maligned public sector—like the Film and Television Institute of India (FTTI) and National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC) contributed to the making of films by Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Saeed Mirza (all FTII-trained), and many others. It is worth remembering that government support is absolutely essential for the creation, promotion, and preservation of art in many forms. When it dries up due to mindless privatisation and reactionary control, the effects are disastrous.

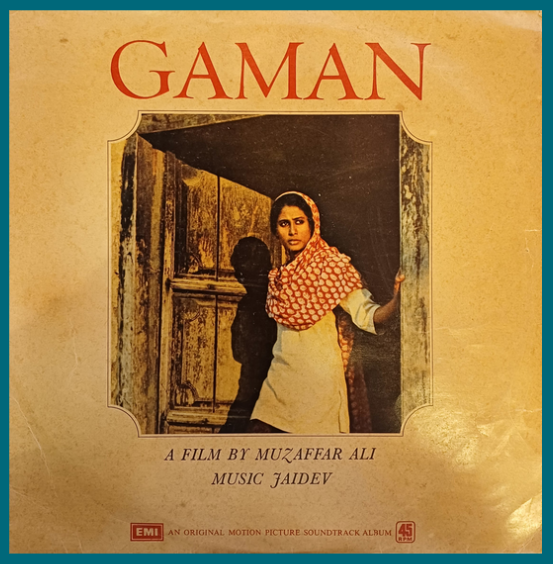

Muzaffar was a talented painter with an amazing aesthetic sense. He decided that this was the time to pursue his calling as an artist and took a year’s leave from Air India to make Gaman. This was, of course, a risky leap in the dark—and I’m happy to say that I did not discourage him in any way. He sketched many of the scenes of the film and was able to persuade the NFDC to give a loan to someone who had neither any experience of nor training in film-making! Film-making was playing a parallel role in my life. Writing, story development, costumes—these became my unasked-for assignments. Wives are expected to contribute a lot of unpaid labour in different ways, and I was no exception.  Image courtesy: Shah music

Image courtesy: Shah music

The central character of Gaman is a migrant from Uttar Pradesh (UP) who becomes a taxi driver in Bombay. Asghar Wajahat, Muzaffar’s closest friend from Aligarh and my comrade, came to stay with us to work on the script. I was happy to contribute to its development. Because of my work in Kurla, several elements found their way into the film. I’m quite proud of the fact that I helped to organize quite a bit of the shooting in Kasaibada. Jalal Agha’s kholi was situated here, and Farooq’s long walk up this filthy hillock brings home the reality of life in Bombay for poor migrants, leaving him devastated.

The other Kurla I worked in—the Kurla of gaalas and workers from Western Maharashtra—was responsible for the scene in which a red-flag demonstration, a lazeem procession, and zanjeer ka matam in Mehmudabad, UP are intersected.

Gaman made Smita Patil and Farooq good friends. Jalal was an entertaining neighbour. We were privileged to work closely with Jaidevji, a man of great talent and ethics. Shahriyar Bhai, possibly the greatest living Urdu poet of the time, came for the first of several long stays at home.

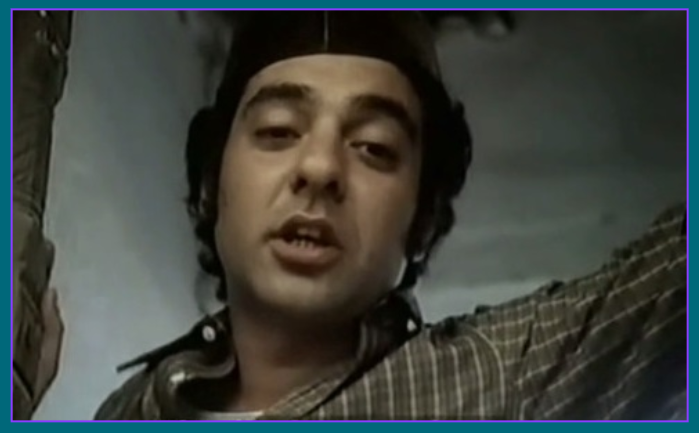

When we went to meet Hiradevi Misra, a pukka Banarasi thumri singer, she said in her pukka Banarasi lehja (accent), “Fees mili to gaana to hum gaa deb, lekin suno, hamaar ek shart hai. Hum acting bhi karab!” (“If I’m paid, I’ll sing the song—but listen, I have one condition: I will act as well!”).  Image courtesy: Screen grab from a YT videoSo she played Jalal’s mother and sang Aa Ja Sawariya in a way that embodied the pain of families separated by the necessity of migration.

Image courtesy: Screen grab from a YT videoSo she played Jalal’s mother and sang Aa Ja Sawariya in a way that embodied the pain of families separated by the necessity of migration.

Shahriyar Bhai’s famous ghazals—Seene Mein Jalan, Aankhon Mein Toofan Sa Kyun Hai and Ajeeb Saniha Mujh Par Guzar Gaya, Yaaron—sung by Suresh Wadkar and Hariharan, brought the alienation and loneliness of migrants in a big, bustling city to life.

Getting to know the actors and coming into contact with all those contributing to this new kind of Hindi cinema was a bonus! Farooq Shaikh, a very committed actor, got under the skin of Imagethe migrant from a UP village. Interestingly, he did not know how to drive! While this made him very convincing in the scenes where his character is learning, it created problems in the scenes where he is actually driving around Bombay, picking up and dropping off passengers.

He and Smita played villagers from UP very convincingly—speaking Awadhi and adopting the typical mannerisms—despite the fact that he was a Gujarati and she a Maharashtrian. Much of the film was shot in Kotwara, Muzaffar’s village in UP. This included a scene in which the actual postman of the village brings the first money order from Bombay to Farooq’s family. The postman looked the part but was so nervous that he mumbled desperately. It needed someone with the genius of Naseeruddin Shah to dub his lines accurately and brilliantly! The friendly atmosphere of the world of “new cinema” in Bombay was such that Naseer happily agreed to do the dubbing despite not acting in the film.

Image courtesy:Wikipedia

Image courtesy:Wikipedia

Jalal Agha, a complete Bambaiyya, played a ‘sophisticated’ villager who had acquired many city slicker mannerisms, with his typical bravado. Playing an earlier generation of migrants from rural Maharashtra were Nana Patekar, with his barely controlled hostility and aggression, Arun Joglekar, Arvind and Sulabha Deshpande—all stars of the vibrant Marathi theatre of the time. The lives of migrants—different waves, their interactions, conflicts, and prejudices—were not only part of our everyday lives in Bombay but part of our own consciousness, since we were migrants too.

Gaman was completed within the loaned amount of Rs. 4 lakhs, for the repayment of which we were hounded for many years! The premiere was given to the Taxi Drivers’ Union and hundreds of taxi drivers attended. Their responses were striking. They could not believe a film had been made about them. They could not understand why anyone else would be interested in their lives.  Image courtesy: Love Life and CinemaWhenever a character spoke Awadhi on screen, there would be some laughter from the audience.

Image courtesy: Love Life and CinemaWhenever a character spoke Awadhi on screen, there would be some laughter from the audience.

In the final scene, Farooq Shaikh, imprisoned behind the iron gate of VT station, hears the whistle of the train he had hoped to board to return to his village. Passengers move like ghostly figures as he watches. He can either board the train and go home, penniless, or stay and send the ticket money back to his wife and ailing mother. He stares ahead, swallows several times, and the train slowly moves off the platform. The taxi drivers watching were riveted to their seats and remained silent for some time. Many emerged red-eyed.

I feel that no effort is made to introduce ordinary people—workers, household help, electricians, plumbers, taxi drivers—to art that, in many ways, deals with their lives. They are not invited to art galleries or film shows; no thought is given to developing their appreciation of what could not only enrich their lives but also help others better understand the value of what they do and contribute to society.

While Gaman was organically linked to my work in many ways, Umrao Jaan was set in opulent, pre-Mutiny Nawabi Lucknow. Based on a famous Urdu novel, it gave me the opportunity to employ many women in Lucknow and Kanpur living in reduced circumstances, but who retained a living knowledge of the clothes and culture of an age that had ended before they were born—passed down through remnants and fragments from their parents and grandparents.

Organising the vast number of costumes that a period film requires was daunting. At a time when I felt completely overwhelmed, I met the wonderful Jennifer Kapoor, who asked me to come over to Prithvi Theatre and open up boxes of clothes used in Junoon, a film of the same period. She said simply, “Just take whatever you like and come back for more.” Her generosity was breathtaking. And although it was thrilling when Rekha won the Best Actress award for Umrao Jaan, I was very unhappy that Jennifer did not get it for 36 Chowringhee Lane. They should have given two awards.

Jeniffer Kapoor in 36 Chowringhee Lane, Image courtesy: Mubi

Jeniffer Kapoor in 36 Chowringhee Lane, Image courtesy: Mubi

Umrao Jaan was financed by someone from the commercial film world, Shri S.K. Jain. This was a strange and not always pleasant experience. It was difficult to accept many of his decisions driven purely by commercial considerations. Jaidevji and the lesser-known singers he had chosen were not acceptable to the producer, which was difficult to communicate.

A young Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) actress, Reeta Rani Kaul—who had worked hard to perfect her Urdu and had even undergone a painful nose-piercing—had to be dropped. A mujra choreographed by Gopi Krishanji had to be included. I personally did not like it much (Dil Cheez Kya Hai)—but the audience did.

We were fortunate that Khayyam Saab became the music director, Ashaji agreed to sing, Prema Narayan played Bismillah, and Kumudini Lakhiaji choreographed not just the mujras—In Aankhon Ki Masti, Yeh Kya Jagah Hai Doston—but also the movements that accompanied seated ghazal renditions.

Kumudiniji had grown up in Lucknow and was happy to return for the shooting. I will never forget how Bansi-da (Chandragupta), an art director of genius, cleaned every marble pillar of the Baradari with cotton wool dipped in nail polish remover, making the entire place magical. The first day of shooting ended in disaster. Rekha insisted on wearing a thin anklet instead of the heavy ghungroos the mujra demanded. When she refused to take direction courteously, I—unaware of the importance of keeping stars happy—told her off. She went to her hotel in a huff, and Muzaffar was convinced the film was over. I stuck to my guns.

The next day, everyone waited nervously. Rekha arrived, having gone to the Chowk in a burkha to buy traditional ghungroos—about a hundred brass bells stitched to red cloth backed with leather. She wore them in every mujra scene despite bruised ankles. Khayyam Saab and I took to each other for a strange reason. Before Independence, he had worked with progressive film groups (Garam Coat, etc.) and, despite being a devout Muslim, decided to stay in India after Partition because of his commitment to secularism. His wife, Jagjit Kaur, a practicing Sikh, sang young Umrao’s engagement song.

Image courtesy: The TribuneI had suggested to him that Ashaji sing in a lower key, more suited to a tawaif than the typical Bombay style. He refused to make the request but took me to meet her. I was intimidated, but I made my suggestion. Ashaji looked at me quizzically, smiled, sang an antara in a lower register, then stopped and asked, “Theek tha?” Well—she did win the National Award. I’m told she still speaks fondly of me.

Image courtesy: The TribuneI had suggested to him that Ashaji sing in a lower key, more suited to a tawaif than the typical Bombay style. He refused to make the request but took me to meet her. I was intimidated, but I made my suggestion. Ashaji looked at me quizzically, smiled, sang an antara in a lower register, then stopped and asked, “Theek tha?” Well—she did win the National Award. I’m told she still speaks fondly of me.

One other contribution I take credit for: insisting that my darling Shaukat Apa play Khanum. Muzaffar had wanted her to play Umrao’s mother, a minor role. But as Khanum, she brought great heft to the film—and, to my eternal delight, she said she liked her costumes better than Rekha’s!

Getting money out of the producer’s representative in Bombay, Bhaiji, was gruelling—and often fell to me. I hated it. But the truth is that Umrao Jaan was a risky venture: a woman-centric film, carried by a female star, at a time when male-centric, hero-driven films dominated. If costs had not been kept under strict control, the film might not have even been completed. Fortunately, Umrao Jaan emerged as a gorgeously mounted film that recovered its costs—but only because of Rekha not demanding her usual fee.

Filmmaking, for me, was something I had to do—my unpaid domestic labour! I enjoyed it and was quite conscientious. But my political work, as a Party member and a woman activist, was always my real work.

0 comments