Economy

How BJP Trapped Crores of Poor Women into Usury Under the Cover of Financial Empowerment

Anusha Paul

Published on Sep 08, 2025, 01:32 PM | 10 min read

In March 2014, on the occasion of International Working Women’s Day—a day rooted in the militant struggles of women workers against capitalist and patriarchal exploitation—the then contender for Prime Minister Narendra Modi stood before the country with a cup of tea and a slogan: “Bahut Huwa Naari Par Vaar, Ab Ki Baar Modi Sarkar” (Enough of attacks on women, it's time for Modi Government.”

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), tied to the patriarchal cultural nationalism of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), was suddenly speaking of women’s safety and economic empowerment. The “Chai Pe Charcha” was broadcast live to over 1,500 locations across the country—particularly targeting rural, illiterate, and working-class women.

In the 2014 Lok Sabha campaign, Modi repeatedly told poor women that economic freedom is essential for women’s empowerment, praising them as disciplined borrowers and promising greater credit for self-help groups (SHGs) and cottage industries.

Soon after coming to power in 2014, the BJP-led Union Government launched the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) on August 28. This was projected as a revolutionary step toward financial inclusion, aiming to bring the unbanked population, especially women, into the formal financial system.

According to the Ministry of Rural Development, 11 crore rupees have been disbursed to SHGs through formal institutions under the Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana - National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) as of July 2025.

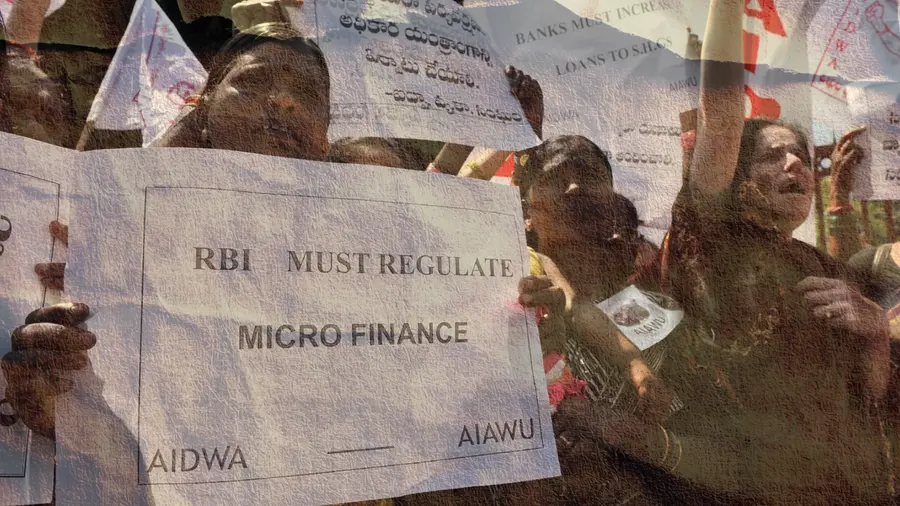

On August 24, 2025, the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA)—India’s largest women’s organisation with over 10 million members—released a national report after a year-long survey of 9,000 women across 21 states. Far from being a tool of empowerment, the expansion of credit has locked large sections of rural and working-class women into a cycle of indebtedness, coercion, and financial extraction.

The report shows that this expansion was driven less by a commitment to women’s economic rights and more by the logic of private financial capital entering new markets of extraction.

While the withdrawal of public sector banks from direct lending began with the neo-liberal turn of the 1990s, the process took a qualitatively different form under the Modi regime. Since 2014, there has been a systematic dismantling of direct institutional lending to small borrowers and SHGs.

Promoting Usury Under The Guise of Credit Expansion

Instead of giving loans directly to women, public sector banks now channel funds to Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) and Micro-Finance Institutions (MFIs), typically at interest rates of 10 to 11%. These NBFC-MFIs then re-lend the same money to poor women at rates ranging from 22% to 26%. AIDWA’s survey found that 40% to 60% of the women borrowers in different states were unaware of these interest rates.

Punam Toppo, a 35-year-old Adivasi woman from Jharkhand and a domestic worker, turned to MFIs because her wages were not enough to run her household.

“In 2022, I took a loan of 2,983 and returned it with 20% interest. In 2023, I took another loan of 73,801 at 22% interest, and then a third loan of 1,640 with 25% interest,” she said.

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Microfinance Loan Directions, 2022, removed the existing caps on interest rates, allowing NBFCs to set their own rates through their boards. This has trapped borrowers in a debt spiral, forcing them to take fresh loans just to repay old ones.

AIDWA reported that most surveyed women had taken multiple loans. About 32% had borrowed from more than three companies, while nearly 60% had borrowed from more than two. Around 40% of the women had a debt of more than 50,000, while another 40% owed between 1 and 2.5 lakh. This burden is far beyond their capacity to repay monthly EMIs. Further, 50% to 60% of these women were forced to keep their jewellery, house papers, Aadhaar cards, or other personal belongings as collateral, contrary to RBI guidelines that define microfinance loans as “collateral-free.”

RBI guidelines also state that borrowers must be informed about the recovery process before the loan is issued. According to AIDWA’s survey, almost no borrower was made aware of these procedures.

This cost 49-year-old Uma Vinayagam from Puducherry her home. With no steady income apart from her husband’s irregular earnings of 6,000 per month as a musician, she borrowed from Jana Bank to start a home-based shop. But after road expansion work caused her business to fail, she could not repay the loan. Recovery agents began frequenting her home, pasting notices on the door.

On May 12, 2022, officials and police arrived with an eviction order. The whole family — including her elderly in-laws over 75 — was given barely 30 minutes to vacate. Their home was sealed, with all possessions locked inside. The bank then auctioned her house.  Pooja Kumari

Pooja Kumari

Despite RBI guidelines prohibiting verbal or physical harassment during recovery, Pooja, from Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, was not only harassed but also held hostage. She had borrowed 40,000 from IIFL Samasta Finance Limited to repair her vehicle. After making 11 of 24 instalments, she found only seven were recorded. When she stopped paying and demanded correction, she and her husband were summoned.

When she appeared with her husband, officials held her hostage and told her husband to bring money for her release. They even allegedly suggested she commit suicide, offering a rope. Her husband called the police, who rescued her, but took them both to the station and forced them to sign a letter claiming they were not harassed and went voluntarily. They could not read the document, but signed it.

The harassment did not end there. Recovery agents began visiting their home early in the morning, staying until 2:30 a.m., violating RBI rules that prohibit such visits between 7 p.m. and 8 a.m. They even threatened to film her and make the video go viral.

The shame and intimidation are such that women are even driven to suicide. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 7,0374 people committed suicide due to indebtedness in 2022. The actual number is likely higher, as not all such causes are reported.

Suicide and Sexual Harassment

Shamed by the physical and verbal abuse inflicted on her and her husband by Dharmasthala Sangha, a microfinance company, Eramma from Raichur district in Karnataka consumed pesticide. Though she survived the suicide attempt, she collapsed and died from high blood pressure during another visit from recovery agents.

In shock, her husband Parappa, a retired coal worker, became bedridden. Nevertheless, he continued to face legal threats until his death last December.

“Come with me for one night. You will not have to pay the interest for that month,” a moneylender offered Ayesha Nadaf from Sangli district, Maharashtra. She had borrowed from SKS Microfinance to manage household expenses during her husband's unemployment.

Ayesh Nadaf

Ayesh Nadaf

Her refusal brought more harassment. Eventually, her husband abandoned her and their children, telling her to give in to the moneylender’s advances.

“Financial inclusion is a key driver for economic growth and development. Universal access to bank accounts enables the poor and marginalized to participate fully in the formal economy and benefit from its opportunities,” said Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman just days after AIDWA’s report was released.

Alongside this rhetoric, the government released new figures: as of August 13, 2025, there are 56.16 crore Jan Dhan accounts, with 55.7% held by women and 66.7% located in rural and semi-urban areas.

The government also claimed that 6.9 lakh crore was directly transferred into people’s accounts in 2024–25 through various welfare schemes. It added that total deposits in these accounts have now grown to 2.67 lakh crore—around 12 times higher than in 2015.

However, before 2015, the state played a more active role in ensuring welfare through public provisioning—free or subsidised food, education, healthcare, and employment. The shift to direct cash transfers marks a dismantling of that welfare model. Comparing current figures to pre-2015 data is disingenuous because there was no comparable direct transfer system back then.

Moreover, of the 6.9 lakh crore transferred, only 2.67 lakh crore remains deposited—just about one-third. This indicates that even with cash transfers, people are barely able to save. India’s net financial savings hit the lowest in nearly five decades during the 2022–23 financial year, falling to just 5.1% of GDP compare to the 16.9 % in 2013-14. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the number of small borrowers taking loans for daily consumption rose by 5.8% between 2019 and 2023–24.

Kudumbashree Alternative

If the Modi government had genuinely intended to empower poor and working-class women, especially in rural India, it could have emulated an existing, successful model—Kudumbashree. Kudumbashree is not just a self-help group network; it is a democratic, state-supported, community-driven movement of more than 48 lakh women. Instead of routing public sector lending through deregulated private NBFCs and MFIs that charge interest rates as high as 26%, the government could have offered loans at 4%—as the Kerala government already does through the Kudumbashree.

Alappuzha native Jiji Prasad was once landless and homeless, working with her husband in a coir factory. Her life changed in 2000 when she joined Kudumbashree. With a 500-rupee loan, she began selling sweets, then cooked meals for factory workers. Today, she runs a registered catering service under Kudumbashree.

“I now have a small establishment with utensils to serve food for up to 10,000 people, four vehicles, and a team of 30,” she says proudly.

Her story is not an exception. Kudumbashree has over 1.6 lakh women-led enterprises across Kerala. It has proven its worth not only in normal times but during crises too. During the Covid -19 pandemic, when distress borrowings were increasing, yielding huge profits for the usurious NBFCs and MFIs benefiting from the union government's credit expansion schemes, Kudumbashree not only continued to facilitate low-interest loans, but also played a crucial socio-economic role.

Kudumbashree's Super Market

Kudumbashree's Super Market

While the union government’s schemes were limited to digital transfers, Kudumbashree women set up 1,300 community kitchens and fed nearly 90 lakh people across Kerala. They produced over one crore masks, thousands of litres of sanitizer, and PPE kits. They ran help desks, delivered medicines, and provided mental health support and shelter to domestic violence survivors.

During the floods in Kerala in the monsoon of 2018 and 2019, it contributed 11.18 crore to the Chief Minister’s Distress Relief Fund. Kudumbashree’s success is the result of a sustained partnership between the women’s collective and the Kerala Government, led by the Left Democratic Front (LDF), which first introduced the model in 1997 during its tenure.

It has received consistent investment, policy support, linkage to welfare schemes and procurement systems, and recognition as a legitimate development actor. It is not an NGO delivering state services—it is a state-mandated, democratically anchored movement.

By contrast, the Modi government has privileged private financial capital, using the language of empowerment to push unregulated credit while withdrawing state support. Instead of helping SHGs become local economic institutions, it turned them into conduits for usury and extortion. Rather than regulating interest or enforcing responsible lending, it removed caps on interest rates, allowed self-regulation, and encouraged coercive recovery practices.

0 comments