interview

Sickles and Slogans: Women Rising from the Ashes of the Emergency

Anusha Paul

Published on Jun 20, 2025, 06:26 PM | 10 min read

The Emergency was a dark chapter, imposed by a woman leader, and its aftermath saw the Janata Party collapse while the Congress opened doors for the far right. But in the heart of Mumbai’s working-class neighborhoods, women who had lived through and fought against this repression started to rise. With leaders like Ahilya Rangnekar at the forefront, can you share what it was like on the ground during those times? How did those struggles and hopes shape the birth and spirit of the women’s movement?

Once the excitement of the 1977 Lok Sabha election subsided, I became busy juggling my home, a small baby, and my work—both in the women’s organization and in the Party. I continued to work in Kurla, where I had been active during the election campaign and which was part of Ahilyatai’s constituency.

We didn’t have an office in the area, so we used the kholi (tenement) of Com. Eknath Kanchan, a worker at the CEAT Tyre Company, where there was a strong CITU Union. The front part of the room (built on top of a drain, as was common) housed a tailoring shop run by his cousin, Com. Mukund Kanchan, who had been victimized during a major strike at CEAT. Mukund’s wife, Kastura, lived in the village, while Eknath’s wife, Asha, and their small children lived in the kholi.Asha was a strong-willed and brave woman. Once, when some Shiv Sainiks tried to attack Mukund, she came out with the sickle Maharashtrian women used to cut vegetables and was so intimidating that the Sainiks fled.

The area around the Kanchans’ kholi was inhabited mostly by Maharashtrian workers, many of whom had their families with them. Most were textile workers, while a few worked in CEAT and other factories. They all came from the same region in Western Maharashtra. In the lane where the Kanchans, Comrades Nikam (from CEAT), and Deepak (who later joined GKW) lived, there were also two large galas. These were big rooms or halls where several textile workers lived—or rather, slept in shifts. Each had just enough space to roll out a bedding mat to sleep. Once they left for work, they would neatly roll up their bedding, and the space would be used by another worker returning from his shift.

Their days and nights revolved around the sirens from nearby mills that marked each shift. On the walls hung lazeems (sticks with small cymbals) and a big dhol (drum) used during festivals. These galas symbolized the blend of work and cultural life among workers who maintained strong village ties and tried to recreate that life within the small, constricted urban shelters.

A gala was incomplete without a khanavli, a working-class canteen usually run by a woman from the same region as the workers. She would provide two meals daily—jwari bhakri (millet roti), bhaji (vegitables), dal (lentil), and a red chilli-peanut chutney. I often ate in khanavlis or at my comrades’ homes and came to love this food. The wives of gala workers would come to Mumbai for a month or so each year. If possible, the worker would rent the kholi of a comrade going home to his village; if not, a small space would be carved out for her within the gala itself.

Other parts of Kurla were quite different. Behind the Kanchans' area were neighbourhoods populated by UP Muslims, mostly from Gonda and Basti. A few streets away was a small hill called Kasaibada—inhabited mainly by butchers. Likely formed from layers of garbage and malba (construction debris), the area swarmed with people and children amidst refuse. Small huts perched precariously on the hill, while a few houses belonging to affluent Kasai families stood out.

I frequently visited Kasaibada and was soon involved in a battle to stop the open selling of offal in roadside baskets. The stench and filth were unbearable, and the residents were desperate for relief. The ward corporator, a Socialist, was in cahoots with those selling offal, and it took a long, hard struggle to get the Municipal Corporation to act. Fighting vested interests at any level is tough!

The old Bombay–Agra Road formed Kurla’s western boundary, running alongside the Mahim Creek—an essential mangrove for managing Mumbai’s monsoons. Large parts of the creek were already overrun with rapidly expanding huts, mostly inhabited by Muslims from UP. Some worked in textile mills or as daily wage workers and petty traders; many were in the scrap trade and had become relatively well off. Most hailed from the impoverished Gonda and Basti districts.

Many were staunch Wahhabis, and I learned that their forefathers had been drawn to Wahhabism not only for its religious conservatism but also because it promised equality—a return to early Islamic principles. Initially, Wahhabi leaders had opposed landlordism and supported oppressed sharecroppers. Unfortunately, this progressive streak was soon overwhelmed by its conservative aspects.

Our small group of comrades worked hard across different communities, navigating vastly different challenges, and managed to gain recognition and appreciation for the Party. One constant concern was the threat of evictions for bustee (slum) dwellers.

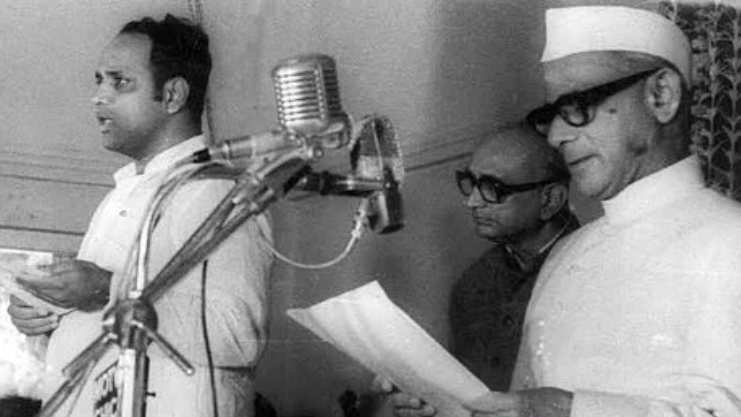

In the 1978 Assembly elections, the Congress retained power with a reduced majority. Sharad Pawar later split the party, allied with the Janata Party—still riding its anti-Emergency momentum—and became Chief Minister. I attended his swearing-in and was amazed at his youth—only 38! Kurla had two Janata Party MLAs from the UP Muslim community, for whom we had campaigned. This enabled us to mobilize people and push for concrete improvements—like a municipal tap here or halting an eviction there.

(Image courtesy: IANS)

But the period of hope that began with the 1977 election results soon descended into confusion and betrayal. The Janata Party, formed in 1976 as a coalition against the Emergency, included the Jan Sangh. Despite the merger, Jan Sangh members retained their RSS ideology and used their newfound political power to further communal agendas. Communal polarization in North India escalated, culminating in bloody riots in places like Jabalpur (MP) and several towns in UP.

Eventually, the Janata Party split over the issue of ‘dual membership’ (being in both the Janata Party and RSS). Our Party supported those demanding an end to this duality, but for many who had worked hard for the Janata Party, the issues were unclear. Disillusionment and anger followed. A belief began to resurface: “Only the Congress can govern this country.” The Congress exploited the situation, installing Charan Singh as Prime Minister, only to withdraw support and bring down his government within months.

The 1980 general election brought Indira Gandhi back to power. Sadly, Ahilyatai lost. Assembly elections followed in Maharashtra, and the Congress regained control. A.R. Antulay became the first Muslim Chief Minister of the state. Ironically, Shiv Sena—despite supporting the Congress during the Emergency and paying a political price—had no MLAs in 1980. Antulay helped revive them by nominating two key Shiv Sainiks as MLAs. The alliance between a Muslim Chief Minister and a communal outfit illustrated the bizarre twists of Indian politics.

Our Party fared poorly in the Assembly elections in Mumbai. Despite having three strong MLAs in 1978—working tirelessly in Bhandup, Worli, and Dharavi—we lost. Kurla fell under the Bhandup District Committee, of which I was a member. We had done significant work in the massive slum along the railway line, ironically named Haryali (Green) Village. But the collapse of the Janata Party government left people feeling betrayed, and we paid the price.

Still, we expanded into new areas and built strong organizations of slum dwellers. Meanwhile, I was increasingly involved in the women’s movement.Soon after the Emergency was lifted, the case of a minor tribal girl, Mathura—raped in a Thane police station—shook the country. Despite clear medical evidence of sexual assault and her being a minor, the High Court ruled the act consensual because there were “no signs of resistance.” This revolting expression of patriarchal prejudice enraged women. Demonstrations erupted nationwide. The Supreme Court’s support of the judgment only fueled the fire.

(Image courtesy: Vibhuti Patel)

Ahilyatai and Com. Susheela Gopalan, then MPs, raised the issue in Parliament. A Parliamentary Committee was formed, with both of them as members, to review laws on rape and dowry. It toured the country, meeting women’s groups, with Left-affiliated organizations playing a key role. Major legal reforms followed—most notably, shifting the burden of proof onto the accused in custodial rape cases. Despite backlash, it was included in the amended law.

Looking back, I’m amazed at the vibrant debates and powerful movements we organized then—especially given how women’s rights (and others) are bulldozed or ignored today. Our women’s organization in Mumbai also played a major role in the Anti-Price Rise Movement led by Ahilyatai and socialist leader Mrinal Gore after the 1980 elections. Prices of essentials were soaring, and hoarding made them scarce. We organized demonstrations and gheraos, demanding sugar, kerosene, and rationed goods—and got improvements in the Public Distribution System. I remember storming a government warehouse where sugar was being hoarded. The panicked official, on the phone with superiors, stammered, “They are here... the women are here! What should I do?”

We took up broader issues too—communalism, domestic violence, and gender-based violence. The Shramik Mahila Sangh led many campaigns.

Around this time, women’s organizations led by CPI(M) leaders were also gaining strength in states like West Bengal and Kerala. In Bengal, women had bravely resisted the 1972–77 period of terror and supported the Left Front’s rise. In Kerala, too, women’s struggles had taken center stage. As a result, it was felt that the time was ripe to establish an all-India women’s organization under the leadership of CPI(M) women leaders.

Discussions were held in Delhi. Com. EMS Namboodiripad gave us invaluable guidance. The organization’s founding principle—that it would fight for the rights of women as women, as citizens, and as workers—owed much to him.

![]()

(Image courtesy: Tricontinental Institute for Social Research)

The first conference of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) was held in March 1981 in Madras (now Chennai). It was a wonderful and inspiring occasion. Dr. Vina Mazumdar, the pioneer of Women’s Studies in India and a staunch Left supporter, inaugurated it. She spoke about patriarchy’s deep roots and its links with social and economic exploitation.

There was a powerful sense of hope and new beginnings. My mother, a delegate, had been part of the early discussions. Her election as AIDWA Vice-President brought special joy—someone who had contributed so much to the freedom struggle would now help shape our women’s movement.

Com. Manjari Gupta was elected President, and Com. Susheela Gopalan became our first General Secretary. Ahilyatai was also one of the Vice-Presidents. What a galaxy of women—freedom fighters, trade unionists, communists, and feminists—stood on that stage as the conference concluded to rousing applause. Many were battle-scarred militants, others had endured jail, persecution, and violence, while countless more were ready to take up the mantle and continue the struggle.

We returned to Bombay fired with zeal to build a strong organisation and movement.

0 comments