Column

The South Asian Quicks, Part 1 (1978-79)

Vijay Prashad

Published on Mar 24, 2025, 11:28 AM | 7 min read

One of the most memorable test matches I ever watched was in Calcutta at Eden Gardens in December-January 1978-79. The West Indies had come to India with a side depleted by Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket money, but it was still a formidable side. Alvin Kallicharran captained the West Indies, which included phenomenal fast bowlers led by Malcolm Marshall. The Bajan fast bowler could surprise any batsman with a fierce bouncer and then in the next ball, with the same action, come straight at the stumps with a deceptively slow delivery. It is for that reason that Marshall devasted line up after line up and won the West Indies the World Cup in 1979. In Calcutta, however, Marshall was muted. At that time, the Indian pitches, by and large, would be prepared to deal with the hot sun and – in Calcutta – the humidity. By the end of the first day the cracks and craters began to appear in the pitch, which always favoured the spin bowlers.

India fielded two top quality spinners, Bishan Singh Bedi and S. Venkataraghavan. Without the benefit of binoculars or well-placed seats, it was still a treat to watch these two men: Bedi with his slow left arm spin and Venkat with his right arm off-breaks. In that test, the selectors had decided to sit out B. S. Chandrasekhar, one of the most captivating and intriguing leg spinners of his generation and brought in an all-rounder to replace him. A young Kapil Dev, the new generation of South Asian quicks, tried his best to get lift off the Eden Gardens’ wicket, but it had been designed for India’s spinners. Venkat took four wickets in the first innings, and then would have bowled out the Windies in the second if Sylvester Clarke and Sew Shivnarine had not sued for bad light. The crowd was exasperated. Shivnarine threw off his gloves on the pitch and refused to go on. In that second innings, Kapil Dev’s bowling partner Karsan Ghavri got four wickets. But to be fair, Ghavri was not a very fast bowler. On Indian wickets, he most often bowled left arm finger spin.

(Test match at Eden Gardens 1978-79)

What was the case for India – the vitality of the spin bowlers – was equally the case for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka in these years. Bangladesh’s young team (formed after 1971) was anchored by the off-break bowling of Syed Ashraful Haque, while Sri Lanka’s D. S. de Silva had a very difficult leg spin that included a crafty leg break googly (he got the only wicket in Sri Lanka’s first one day game in 1975 against the Windies, when he got Roy Fredricks to drive him straight to Bandula Warnapura). There are many theories of spin and the subcontinent, most focused on the weather and the pitches, but others on the low nutritional intake of the players. Was it colonial arrogance that allowed the settler colonial nations to produce the quicks? But then how does that explain the great West Indian fast bowlers (going back to Learie Constantine in the 1920s and the 1930s)?

The binary of brains (spin) and brawn (pace) comforted us, although it could make for extremely onerous test matches where nothing seemed to happen for hours. Anyone who can swing the ball both ways or who can deceive the batsmen with flight and speed after a ferocious runup should not be dismissed as merely strength and not intelligence. I’ve always loved the Australian quick Dennis Lillie’s motto: ‘Bowling fast is about rhythm, sheer will, and a touch of madness’. But also, intelligence.

The King of Pace

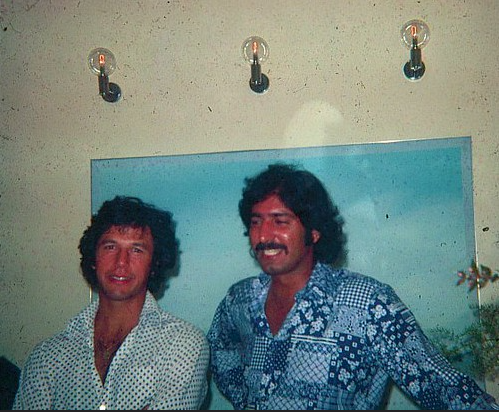

Us kids used to gaze with wonder at the Pakistani fast bowlers – Sarfraz Nawaz and Imran Khan, both with long hair, both Lahore boys, both irreverent. I cannot imagine what it must have been to be in the stands at the Melbourne Cricket Ground to watch Australia and Pakistan play their first test in March 1979 (I only watched the match recently on a very grainy video). The best Australian players had been stolen by Kerry Packer, and yet their team was formidable with Rodney Hogg’s super-fast deliveries taking the first four batsmen in the first innings for just 40 runs. Imran and Sarfraz steadied things with 33 and 35 each. But then Imran swept through the Aussie side, bowling Yallop and Allan Border with unplayable balls. A century by Majid Khan in the second innings, put Pakistan in a good position, leaving Australia to get 382 to win. This is what makes test cricket so exciting. Border made a century, and his team was positioned at 305 for three with only 77 to go. Border was on 105 and Kim Hughes was on 84. The target was within sight.

(Sarfraz Nawaz and Imran Khan)

Even in the grainy video, when Pakistan’s captain Mushtaq Muhammed tosses Sarfraz (whose name means The King) the ball, the flair of the fast bowler suggested something was about to happen. Sarfraz, who had a short and casual run-up compared to today’s quicks, bowled a straight, fast ball right at the stumps; Border tried to pull it onto the leg side, missed the line and was bowled. Sarfraz then took five wickets in thirteen balls without conceding a run. By the time Australia was all out for 310, Sarfraz had taken seven wickets for four runs (three no-balls) in thirty-three balls. In total, in that innings Sarfraz took nine wickets for eighty-six runs, a dazzling feat.

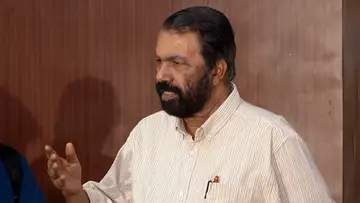

The following year, in 1980, Pakistan toured India. Those were the days, when it was still possible for the two teams to play on the subcontinent and not in Sharjah. Sarfraz was absent, but Imran was coming to his peak. I saw the sixth test in Calcutta, which pitted the fast bowling of Imran Khan and Kapil Dev against each other. Imran’s 5 wickets for 63 in India’s second innings almost won the match for Pakistan, but Pakistan’s could not catch the target of 265 on the last day of the match. This was not the best of the series. That took place in Madras in the previous test. It was perhaps the first time that an Indian fast bowler won a test for his country on Indian wickets. Kapil Dev took 4 for 90 in the first innings and 7 for 56 in the second. Importantly tearing through the best of Pakistan’s batting line up – Mudassar Nazar, Sadiq Muhammed, and Zaheer Abbas when the score was only 33. The ball that got Abbas was a classic Kapil Dev outswinger that caught the bespectacled master for the second time in the test, the first a catch to Syed Kirmani (a duck) and the second to Chetan Chauhan (15). Despite his amazing performance in the 1983 World Cup, which he won for India at the age of 24, Kapil Dev often reflected on this Madras test as the most significant for him.

(Imran Khan and Kapil Dev)

It was also the start of the story of the South Asian quicks, now people such as Jasprit Bumrah (India), Taskin Ahmed (Bangladesh), Asitha Fernando (Sri Lanka), Haris Rauf (Pakistan), Fazalhaq Farooqi (Afghanistan), and Sompal Kami (Nepal), among many others. Today, the wickets in South Asia are not designed for the spin bowlers, and nor are they so slow that the tests would predictably end with a draw. The Indian Premier League (however much it is reviled) has brought a new panache to the state of play and put pressure on groundskeepers to produce new kinds of wickets.

There is something that is lost in these new wickets. Perhaps it is the heterogeneity of the game. Do I long for the day when Bedi and Chandra would spin an afternoon away and harass the best of English and Australian batsmen who were used to much more speed and bounce? Perhaps. But maybe that is just plain nostalgia for something that would make me impatient even then. Cricket came alive for me with Kapil Dev and Imran Khan. When they ran into bowl, I felt the electricity of the game. That feeling remains when I see Bumrah rush in with his back-breaking action, dismaying batsmen with his swing and accuracy.

(Vijay Prashad is the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and chief correspond for Globetrotter)

0 comments