Opinion

Nilambur Exposed Congress’s Alliance with Both Majority and Minority Communal Forces

Anusha Paul

Published on Jun 26, 2025, 02:41 PM | 7 min read

By all accounts, Kerala is India’s secular conscience—a state that held the line while others faltered. It resisted both the muscular majoritarianism of the Sangh Parivar and the narrow identity politics often masquerading as minority rights. Its politics, rooted in social justice and ideological clarity, stood apart from the quicksand of communal calculation.

What do we call it when a coalition that claims secularism as its core value openly allies with a party formed by a theocratic movement? What does it signify when the same political formation quietly accepts support from a far right party whose core agenda is the promotion of Hindutva-driven communalism? And what remains of political integrity when parties that claim to be secular align with communal forces—both majoritarian and minoritarian—just to defeat a common ideological opponent?

The United Democratic Front (UDF), at least claimed by them to be a secular formation, aligned openly with the Welfare Party of India—an electoral front formed by the Jamaat-e-Islami Hind in 2011—and directly benefited from the quiet support of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) vote base in the Nilambur by-election. This unlikely convergence of political forces—each with its own ideological baggage—was driven by a singular objective: defeating the Left Democratic Front (LDF) and its candidate, M. Swaraj.

To appreciate the full implications of this by-election, it is important to first understand the ideological positions at play. Hindutva communalism, as practised by the Sangh Parivar, is premised on an exclusionary ideology that poses a direct threat to India’s constitutional secularism. Its rise has been rapid and visible. Minority communalism, on the other hand, has often escaped equivalent scrutiny, especially when it cloaks itself in the language of victim-hood and minority rights.

The Jamaat-e-Islami, the ideological parent of the Welfare Party, has a long record of opposing democratic institutions. Historically, it viewed democracy as un-Islamic and advocated the establishment of an Islamic state. While its Indian wing has publicly softened these positions in recent decades, its foundational ideology continues to inform its political approach—emphasising religious identity and community-based mobilisation. The creation of the Welfare Party of India in 2011 was an attempt to translate this religious social work into political influence, while maintaining a veneer of constitutional participation. Yet the communal undercurrent remains.

The UDF’s decision to accommodate the Welfare Party during the Nilambur by-election reflects their readiness to compromise secular values when convenient. At the same time, BJP leaders, while vocally opposing “minority appeasement” across India, quietly facilitated a transfer of votes to the UDF in Nilambur. This is the same BJP that frequently condemns the Congress for its supposed softness on radical Islamic groups.

Nowhere was this cynical alignment more visible than in the treatment of M. Swaraj. A young CPI(M) leader known for his clarity on secularism and his consistent criticism of both majority and minority communal politics, Swaraj became the common target of coordinated hostility. What followed the announcement of his candidacy was not mere political rivalry, but a joint effort—from both right-wing Hindu and Islamist quarters—to marginalise a figure who challenged their communal narratives.

In the days following the results, senior political leaders—not fringe voices—engaged in online trolling and issued inflammatory statements against Swaraj. The tone of the post-election commentary has been marked by a startling lack of restraint, and a complete departure from the standards of mature democratic discourse. Kerala’s political space, long celebrated for its robust yet respectful ideological debates, appears to be shifting towards a more toxic, polarised culture.

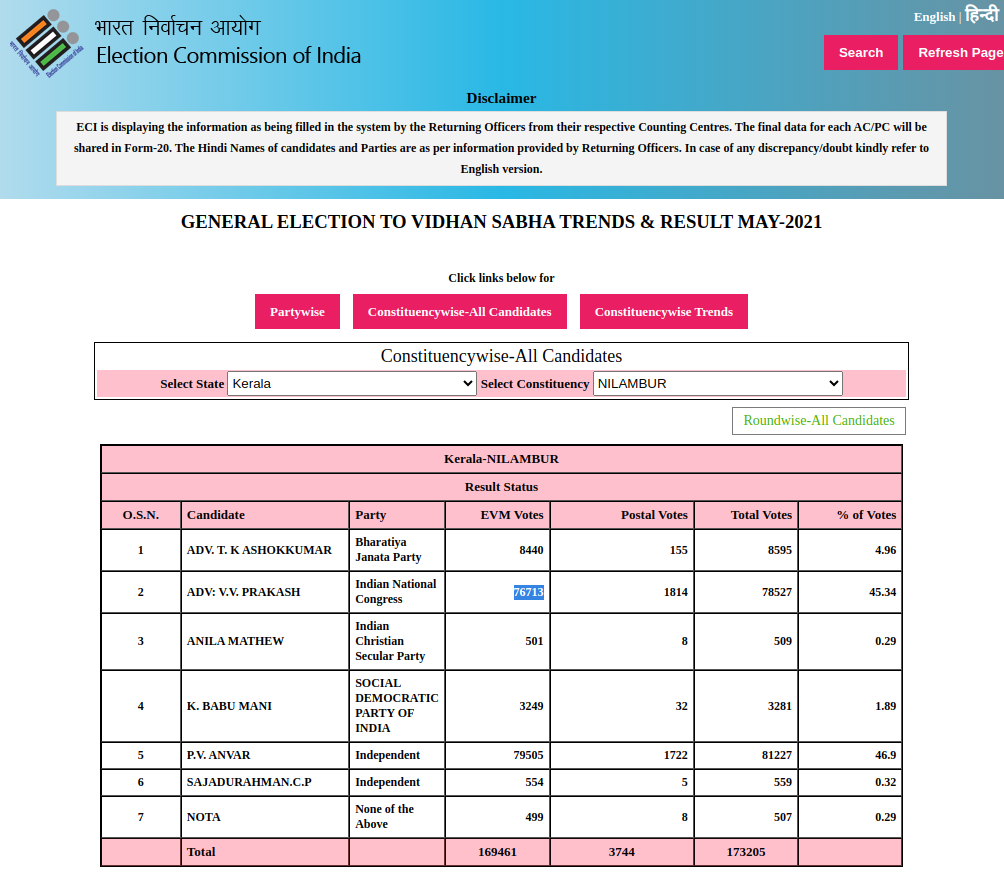

Contrary to the right-wing media narrative, this by-election result was not the sweeping rejection of the LDF that some have claimed. A closer look at the numbers tells a different story.

UDF candidate Aryadan Shaukat won the seat with 77,737 votes, but this was fewer than the 78,527 votes secured by the UDF candidate V.V. Prakash in 2021. This, despite an increase of 3,000 additional voters participating in the by-election. By any reasonable metric, this is not a mandate—it is a reduced margin wrapped in an inflated narrative.

In contrast, the CPI(M)’s M. Swaraj secured 66,660 votes, a significant jump from the 29,915 votes polled by the LDF in the 2024 Lok Sabha re-election. This represents an increase of over 23,000 votes, achieved under the pressure of communal polarization and a broad opposition alliance. Swaraj did not lose support; he gained it. The LDF, though not victorious, demonstrated resilience and ideological clarity, gaining ground rather than ceding it.

The BJP’s vote count collapsed—from 17,520 in the 2024 Lok Sabha election to just 8,562 in this by-election, a deliberate decline of 8,958 votes. The BJP was not initially planning to contest the seat. But just a couple of days before the nomination deadline, Mohan George—formerly with the Kerala Congress (J)—joined the BJP and was fielded as its candidate. George later openly admitted that the BJP’s votes were redirected to the Congress in a calculated effort to defeat Swaraj.

That a party like the BJP—so strident in its denunciations of “love jihad,” “minority appeasement,” and radical Islam—would strategically enable a Congress-Welfare Party alliance in Nilambur speaks volumes. The Hindutva communalism of the BJP and the Islamist fundamentalism of groups like the Welfare Party are less opposites than mirror images—each mobilising identity, fear, and grievance for political gain. In Nilambur, the facade of ideological conflict gave way to the logic of sectarian arithmetic.

To fully understand this development, one must revisit Nilambur’s political history. The constituency was created in 1965, during a time of significant ideological churn. The Communist Party had split nationally, and the Indian National Congress was fracturing in Kerala. In that inaugural election, K. Kunhali,of the CPI(M) defeated Aryadan Mohammed of the Congress. Kunhali,repeated his victory in 1967.

In 1969, Kunhali, was assassinated—shot dead in an act of political violence that marked a tragic first in South Indian legislative history. Aryadan Mohammed, who had been defeated twice by Kunhali, was named as an accused. That event altered the course of Nilambur’s electoral future. The CPI(M), deeply affected by the loss, was unable to win the seat under its own symbol for decades.

In the early 2000s, the UDF’s hold on Nilambur began to weaken. P.V. Anvar, an independent candidate supported by the LDF, won in 2016 and 2021, signifying a shift in voter sentiment. His resignation in January 2025, after rifting from the LDF, led to the current by-election. While the Congress framed the result as a “return” of Nilambur, the voting data tells a story of diminished influence—not restored dominance.

The LDF, far from being ousted, showed signs of growing support. The increased vote share for Swaraj reflects a constituency that, while electorally split, remains receptive to secular, issue-based politics. The attempt to present this by-election as a public referendum against the LDF government ignores these complexities.

More importantly, this election should prompt reflection. When communal entities—both majoritarian and minoritarian—can dictate electoral outcomes by forming tactical understandings with mainstream parties, the foundational values of Indian democracy are under threat.

Kerala, with its high literacy, history of progressive movements, and vibrant civil society, is uniquely positioned to resist this drift. But resistance requires vigilance. It requires that secular parties reject alliances with ideological forces that thrive on division. It requires that political critique be grounded in policy, not propaganda.

The Nilambur by-election is not just about one seat. It is a warning that if the convergence of communalism and opportunism continues unchecked, Kerala risks losing the very secular fabric that once set it apart.

0 comments