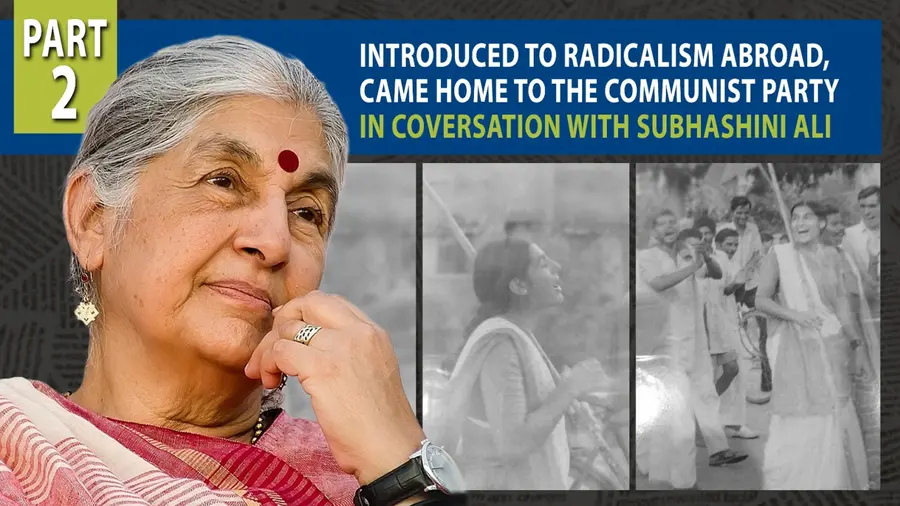

Introduced to Radicalism Abroad Came Home To The Communist Party

Anusha Paul

Published on Mar 31, 2025, 05:43 PM | 8 min read

After coming to India and deciding to be a trade unionist with the CPI(M), drawing from your experiences as part of the global student movement in the USA, how did you navigate the political turbulence and revolutionary fervor of the early 1970s, and what was your learning experience as a young woman trade unionist during that time?

There was very little to compare between my experiences as an activist in the US and my work as a trade unionist in Kanpur upon returning to India. The only similarity was the experience of the class nature of the State. In the US, there were still illusions about the country being the "land of the free.” I was part of a small organization called the Labour Committee, distinct for studying Marxist classics and analyzing demands and slogans.

One of our key slogans, "Tax Profits, Not Wages," caught the attention of authorities. We also conducted intensive leafleting campaigns around predominantly black public high schools, highlighting the economic exploitation of the black community as part of the broader working class.

I recall being arrested during one of these campaigns, an unexpected experience since leafleting was common. The police let me go, assuming I was an “ignorant” Indian. Others were not so lucky. Our shared apartment in Philadelphia was raided by the police and FBI, accompanied by a TV crew. They planted explosives in our freezer, then "discovered" them on TV.

They confiscated books, including Lenin's writings (which weren’t even banned), and arrested four comrades—three men and one woman. Four comrades—all "Red Diaper Babies" (children of Communist Party members)—were arrested and nationally televised. It took months to raise bail, partly through a fundraiser by ex-CP members. The case dragged on for decades before a court finally exonerated them, condemning the government’s deceit.

When I got involved in trade union work after returning to India, my illusions about democratic governments quickly shattered. I was arrested along with 50 women from textile mill workers' families during a campaign to reopen a closed mill where their family members had worked. The government’s violent repression of our peaceful movement, from lathis raised during processions to the conditions in jail, offered invaluable lessons in class politics.

As a young woman trade unionist organizer, I faced sneers from my opponents and the media. They mocked me with slogans like Sahgal mill bandh karvayein, uski beti chalu karvayein, but never hostility from workers. The workers and their families—they were understanding, as the most working class are. They saw the bigger picture. My privileged background and the respect my parents earned in the city for their contributions during the INA movement—my mother, in particular, for her medical services also added up to that.

I had always lived near the mills. The city's air was thick with the smell of beedis, tea, and the dust of industrial labour. While I was familiar with this world, it always felt distant. Now, I was trying to join it, knowing I could never fully integrate, but at least I had chosen a side—the workers’ side.

I often traveled in rickshaws toward a narrow lane off Mall Road, near the dry cleaners we used, leading into Kurswan, a neighborhood marked by poverty and overcrowded homes. Comrade Ram Asrey, the district secretary of CPI(M), lived in one of those crumbling houses and had just returned from exile. He embodied the ideal communist leader—an orator, writer, and avid reader—and under his guidance, I began exploring the working-class world of Kanpur. We held meetings at mill gates and interacted with workers in the tea stalls that surrounded them.

At this time, many textile mills in Kanpur were closing, creating fear among workers in the remaining factories. One of the closed mills, New Victoria Mills, had been managed by my father. Asrey, leading the Suti Mill Mazdoor Sabha, spearheaded a movement to push for nationalization and reopening. Despite opposition from other unions, the unemployed workers supported the idea. We organized a jail bharo protest, and I was tasked with organizing a group of women to court arrest.

For two weeks, I visited bastis and ahatas, where workers from Victoria Mills lived, seeing the extreme poverty and appalling conditions. In the end, over 50 women, from various backgrounds, joined the protest. We marched to the district court and were sentenced to a week in jail.

This victory led to the nationalization of the mill, a historic win for the workers. Following this, I became involved in the JK Rayon Workers’ Union and later helped form a union at the IEL Fertilizer Factory. Strikes in both factories led to significant gains for the workers.

Before the IEL strike, I was arrested with two of my male comrades, Aravind Kumar and R.K Das. Spending the night in jail was daunting, but the woman guard, initially intimidating, turned out to be surprisingly kind. Later that year, the JK Jute mill workers launched a protest demanding a wage increase. I interacted closely with workers from Bihar, the majority of the workforce, and met Ramrati, one of the few female jute workers. Every morning, before the first shift, she would stand outside her room, holding a phukni (an iron tube used to light the stove), daring any strike-breaker to cross her path.

Through these struggles, I began to understand the role of the police and administration in protecting the powerful, which deepened my belief in class struggle. Comrade Jyoti Basu’s insistence that the police should not be used as strike-breakers gained new significance in my understanding. The political unrest in West Bengal after the United Front government was dismissed in 1970 marked a turning point. Despite the Congress party’s victory in the March 1971 elections, the CPI(M) gained ground, becoming the largest party in the state assembly.

In contrast, the CPI, which had contested against the CPI(M), performed poorly. The election period was marked by widespread violence, with three candidates tragically losing their lives. The Congress leveraged its political influence to establish a government, excluding the CPI(M). However, this government was short-lived and was soon replaced by president’s rule. Over time, attacks on the CPI(M), its supporters, and affiliated trade unions became increasingly severe.

In Kanpur, Comrade Shiv Verma, a former associate of Bhagat Singh, was our candidate for the Lok Sabha. This was my first experience with election campaigning, but we only managed 5,000 votes. The Congress, consolidating power, began targeting unions and their supporters. G.S. Bajpai, the Uttar Pradesh labour minister, openly declared himself an enemy of unions, leading to the lock-out of the IEL, JK Rayon, and jute mills. These attacks on the workers were part of a broader campaign against the working class.

The IEL lock-out lasted for 52 days, during which we marched the 18 kilometers between the factory and the district court. In the final weeks of the lock-out, along with union leaders, I was in Delhi, where we held several discussions with cabinet ministers responsible for labour and fertilisers, as well as with the management. During one of these meetings, when we mentioned some assurances made by a minister, a representative of Indian Explosive Ltd (part of the ICI UK group) scoffed, saying, “That dog won’t dance!” This derogatory remark epitomizes the kind of power multinational corporations hold over governments in the Global South, even over Indira Gandhi’s government.

In 1971, I played a role in forming a new union for electricity workers, with Comrade. Pradeep Srivastava, an engineer from Panki Power House. We would arrive at workers’ colonies, seeking out potential sympathizers and comrades, and, surprisingly, we often found them! Shortly after the union was established, a statewide strike was called by the older, established unions.

Comrade Daulat, my colleague, and I were tasked with going to the Power House in Kanpur to ensure that the workers went on strike. We had been on the run from the police for two days before this, and I had to disguise myself by wearing a burkha. The Power House was surrounded by the police, and I stood in front of the gate, holding a plastic basket with a small tiffin. As the shift ended, I climbed onto a stool in front of a tea shop and gave my speech, and the strike began. By then, it was quite dark, and workers, not wanting me to get arrested, quickly pushed me into a small room behind the teashop. From there, I somehow made my way through a maze of narrow alleys, where I truly understood the meaning of the word ‘solidarity,’ as I found a helping hand at every corner.

The attacks on the working class in Kanpur were part of a broader assault that began that year. In 1971, the victory of the Indian Army over Pakistan and the declaration of Bangladesh’s independence elevated Indira Gandhi’s influence, but it was also the beginning of a period of repression, setting the stage for the Emergency in 1975. The attacks we faced in Kanpur were just a small part of a broader assault on the working-class that began!!

0 comments