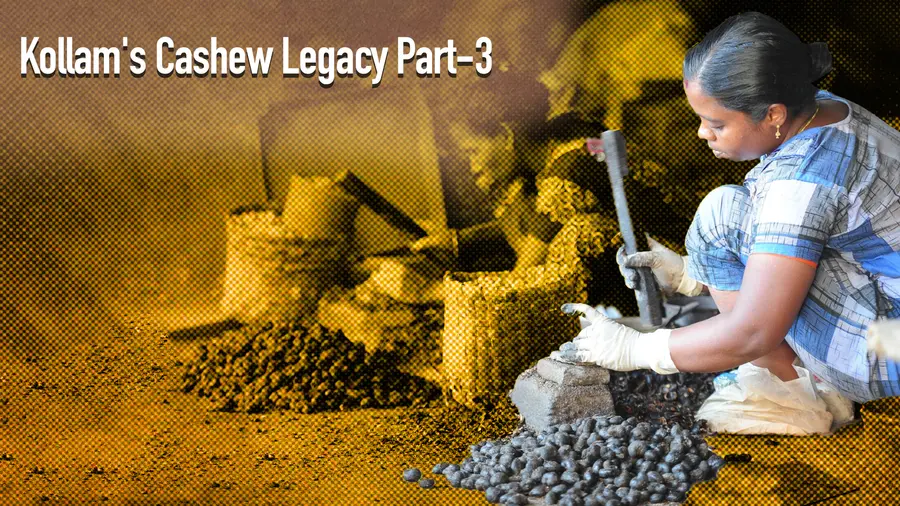

People's Movement

From Chains to Change: Women, Workers, and the Revolutionary Fight for Public Sector

Anusha Paul

Published on Mar 18, 2025, 07:32 PM | 7 min read

Despite the Communist Party’s rise to power and the implementation of several pro-labour policies, the factory owners continued to resist the advancement of workers' rights. This resistance persisted even after the workers' victory in the long legal battle from 1951 to 1957, known as the Cashew Workers’ Magna Carta. The AITUC and UTUC mobilized protests, rallying workers to demand what was rightfully theirs.

E.M.S. Namboodiripad (EMS) and the Communist-led government did not oppose these protests. On the contrary, EMS publicly supported them, urging workers to recognize that the struggle for governance and the fight for workers’ rights must go hand in hand. Workers had to organize, resist, and fight for the implementation of the minimum wage and DA. However, the police force, which remained deeply firm in the interests of the ruling class. Acting as a tool of the bourgeoisie, the police conspired with factory owners to undermine the workers’ struggles and disrupt the efforts of the government.

Seeing an opportunity to weaken the Communist-led government, the UTUC redirected the workers’ struggles to attack the Communist Party. This culminated in a hunger strike at the Hindustan Cashew Products Factory in Chandanathope, led by key leaders such as N. Sreekandan Nair, T. K. Divakaran, T. M. Prabha, and K. P. Raghavan Pillai. The workers succeeded in bringing the government to the negotiating table, leading to a resolution of the dispute. However, the factory owner, Ramachandra Naik, shut down the factory and took the cashew nuts. In response, the workers began picketing, only to be met with brutal force from the police, who had already conspired with Naik.

The police subjected the workers to a lathi charge and later opened fire on them, in a clear act of state repression against the class struggle. This was not an isolated incident but part of a broader campaign to undermine the Communist Party’s leadership of the working class and to stifle the growing unity of workers. Inspired by Karl Marx’s revolutionary call—"Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains"—the workers were beginning to break free from their chains, realizing their collective power.

It was no accident that the ruling class, aware of the strength of the Communist-led workers' movement in Kollam—an area home to cashew, coir, and cotton mill workers—sought to crush it. The strength of the workers in Kollam posed a direct threat to the capitalist system. This fear led to the Vimochana Samaram (Liberation Struggle), an alliance of bourgeois and reactionary forces led by the Indian National Congress, Praja Socialist Party, Revolutionary Socialist Party, Kerala Socialist Party, and the Muslim League, all rallying against the Communist government in Kollam’s soil.

In this charged atmosphere, two UTUC workers, Raman and Sulaiman, were murdered. This tragic event was exploited to further weaken the government and fuel the counter-revolutionary movement. The UTUC joined the Liberation Struggle, turning the deaths of the workers into a rallying cry against the Communist-led government. Another protest soon followed in Palkulangara, where workers from the APMG Factory, led by the AITUC, protested the non-implementation of the 1957 cashew workers' rights. When workers confronted factory owner Sreedharan, the police locked them inside the factory and launched a brutal attack. These two incidents were used to turn public opinion against the Communist government, further eroding workers’ solidarity.

Fearing the growing strength of the Communist movement the central government—acting as the representative of the capitalist class—dissolved the state government on July 31, 1959. This was a direct assault on workers’ rights and their ability to govern themselves through a government that represented their class interests. The anti-Communist propaganda succeeded, and in February 1960, Pattom Thanu Pillai, a puppet of the bourgeoisie, became Chief Minister. His government, representing the factory owners and the ruling class, immediately began undoing the gains that workers had fought so hard for, while inflation further squeezed the working class.

Despite this setback, the AITUC continued to resist, demanding a revision of the minimum wages. In April 1960, the government reluctantly agreed to negotiate, but after prolonged talks, it became clear that the factory owners were unwilling to agree. Pattom Thanu Pillai asked the unions to withdraw temporarily, promising to negotiate with the factory owners within a week. However, the workers, unsatisfied with mere promises, resumed their protests. In the end, the factory owners were forced to agree to the workers' demands, conceding the implementation of the revised minimum wages.

At this time, the shelling and peeling rate was set at 9 paise per pound, while time-rate workers were to receive 1 rupee and 40 paise, and men earned 2 rupees and 50 paise. However, these victories were temporary. As the class struggle continued, new challenges arose, including the national debates about India’s stance on the 1962 Indo-Sino war.

The national divisions within the Communist Party also deepened. The 1961 Vijayawada Congress failed to present a political resolution, and the India-China issue further splintered the Party. Leaders of the CPI, such as AKG and EMS, argued for internationalism, asserting that the people of India should stand together for internationalism rather than taking sides. They contended that India should not stand against China or itself but should instead engage in dialogue to resolve the issue rather than waging war, especially when the newly formed nation was yet to stand on its feet.

This split gave birth to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPI(M). The formation of the CPI(M) marked a clear ideological break, but also a practical one. The unity of the cashew workers, which had been a strength under Communist leadership, was now fractured. While the CPI(M) sought to preserve this unity, the AITUC and the CPI refused to include them in the Central Cashew Workers’ Council, ultimately labeling CPI(M) leaders as "anti-nationals" and agents of China. Following the split, CPI(M) leaders were arrested, and neither the AITUC nor the Cashew Workers' Council raised their voices in protest.

The closure of several cashew factories in Kollam and their relocation to other states were a direct consequence of the split. The factory owners, in collaboration with the reactionary state, crushed the workers’ struggles and shifted operations to regions where they could exploit workers without facing organized resistance. The AITUC, now under the influence of the capitalist class, failed to protest these closures and, in some cases, even supported the factory owners.

In the wake of escalating food scarcity and the closure of several cashew industries, political turmoil engulfed the region. The 1965 Assembly elections saw no party secure a majority, leading to the continuation of Governor's rule. Amidst this crisis, the CPI(M), a relatively new force, secured 40 out of 73 seats contested, including a significant victory in the Cashew Belt. This achievement was all the more remarkable given that the party’s leaders were either imprisoned or underground, and the party lacked a formal union. These struggles of the workers ultimately paved the way for the CPI(M) to form the government in 1967.

In the same year, the CPI(M) laid the foundation for the Kollam Jilla Kashuvandi Thozhilali Union (Kollam District Cashew Workers Union), a district-level workers' union. By 1968, the union held its first annual general meeting and elected its leadership. While women had always been the backbone of the cashew industry workforce, this period marked a historic moment—the election of Mandakini as the Vice President of the Union, the first woman to assume such a position.

This period saw a powerful uprising by the cashew workers, who fought for their rights and played a crucial role in the establishment of the Kerala State Cashew Development Corporation Limited (KSCDC). The workers' collective struggle for control over the industry was a critical moment in the broader fight against capitalist exploitation and for the public ownership of key sectors of the economy.

To learn more about the next phase of this workers’ struggle and the continued legacy of Kollam’s cashew sector, stay tuned to Deshabhimani. This is Kollam’s Cashew Legacy – Part 3, where we dive deeper into the largest sector of women and workers based in Kollam, and their fight for control of the cashew industry.

0 comments