National

The Coup That Never Was: How the IB Built the Case for Emergency

Sreekumar Sekhar

Published on Jun 25, 2025, 01:20 PM | 6 min read

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who had issued the Emergency notification on June 25, 1975, needed a status report to justify the declaration. She assigned this task to the Intelligence Bureau (IB). The mission was to ‘find out’ that the Emergency was not a consequence of the court verdict against Indira Gandhi and the protests that followed.

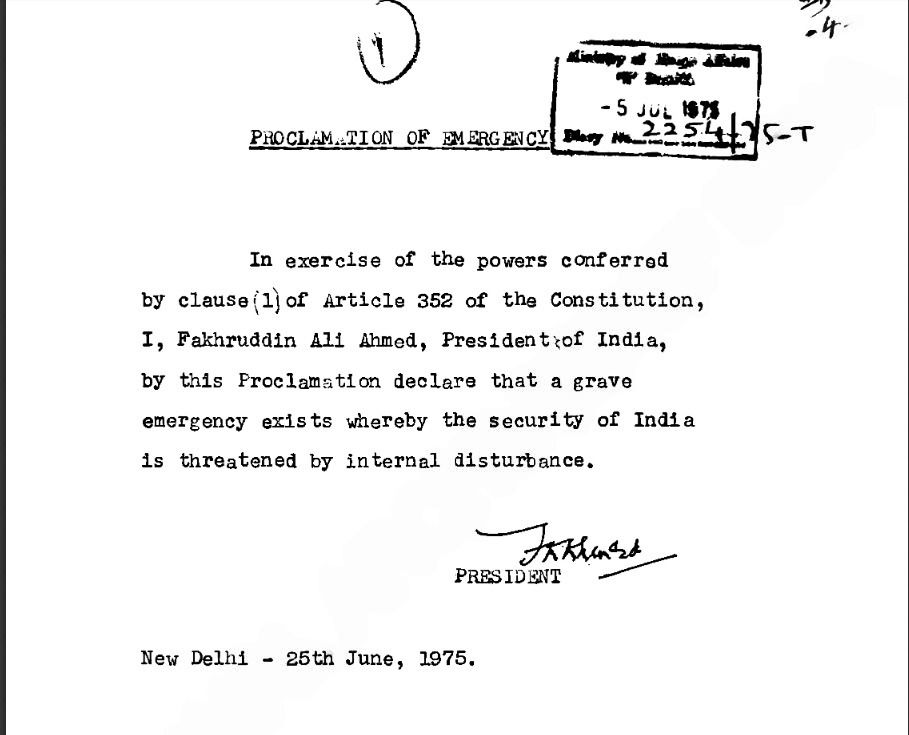

To support this, the President’s one-line notification was issued: “In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (1) of Article 352 of the Constitution, I, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, President of India, by this Proclamation declare that a grave emergency exists whereby the security of India is threatened by internal disturbance.” Information to substantiate this claim of a ‘grave emergency’ was urgently required—and that is what the IB sought to fabricate.

The Intelligence Bureau submitted its report on July 11, 1975—sixteen days after the Emergency was imposed. Titled The Threat of Grave Internal Disturbance: The Need for the Proclamation of an Emergency, the 34-page document, marked ‘Top Secret’, is now available in the National Archives.

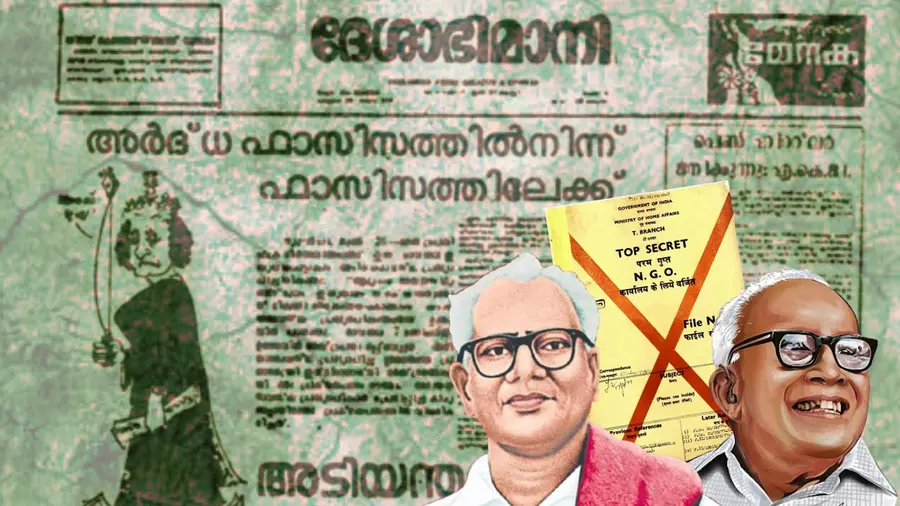

The report claims that the opposition parties were preparing for a major coup in the country. It also makes several allegations against the Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPI(M), which is mentioned 23 times. The IB further accuses Deshabhimani, the CPI(M)’s mouthpiece in Kerala, of inciting unrest.

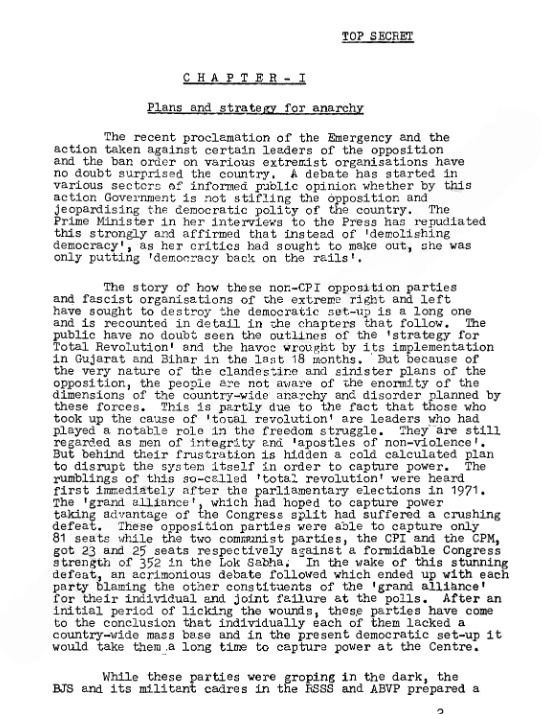

Repeating Indira Gandhi’s claim, the report suggests that the opposition and the Left, along with extremist forces (opposition parties other than the CPI), were conspiring to destroy India’s democracy—necessitating the declaration of Emergency. In support of this, the report presents ‘evidence’ from various states, interpreting the labour strikes and mass protests of the 1970s as part of an orchestrated, imaginary coup.

It argues that the opposition, frustrated by its 1971 election defeat, was driven to launch a ‘coup attempt’. Central to this narrative is Jayaprakash Narayan’s ‘Total Revolution’, which the IB identifies as the main threat. The report’s focus on the CPI(M) begins by noting that the party had 25 members in the Lok Sabha at the time.

On its fourth page, it states: “The CPI(M) found in him a new 'Messiah' in whose alliance they thought they would be able to break their political alienation and isolation in the West Bengal scene.”

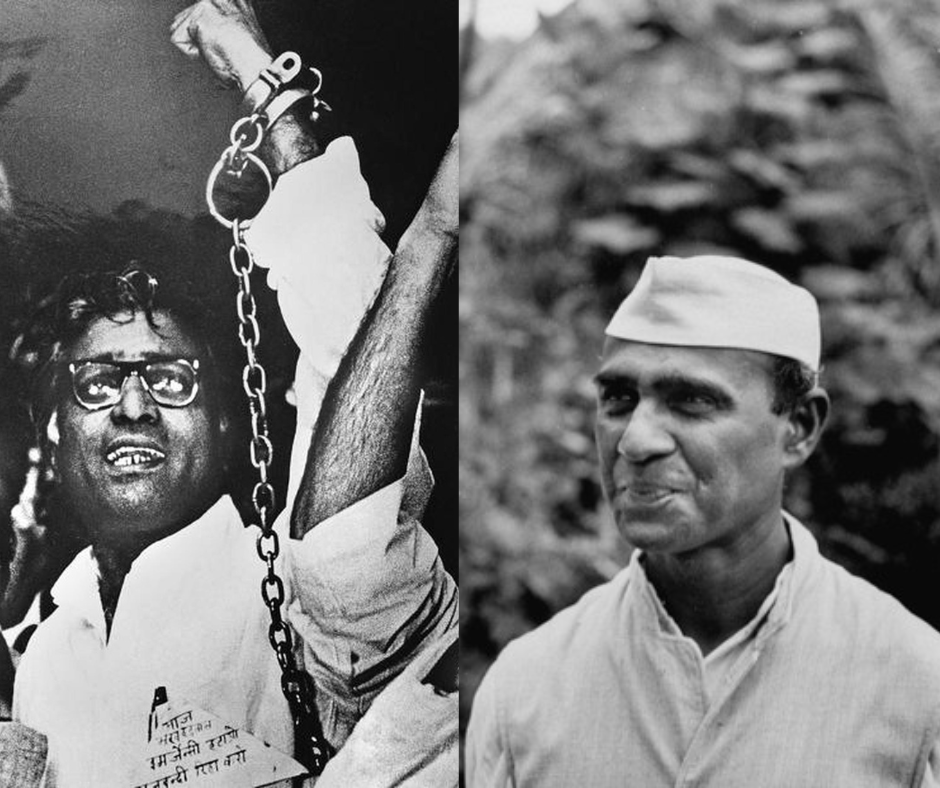

The report goes further, alleging that the CPI(M) orchestrated the replacement of Peter Alvares, a ‘moderate’ leader of the All India Railway Men’s Federation, with George Fernandes as its president. According to the IB, the 1974 railway strike was not a workers’ protest but a politically motivated strike aimed at toppling the government.

(Image courtesy: Google. George Fernandes on the left and Peter Alvares on the right)

The CPI(M) and other parties are also blamed for the student strikes and labour unrest that erupted in Gujarat on April 24, 1973. Following these protests, the Gujarat cabinet resigned in February 1974. The report claims that opposition forces were responsible for the dissolution of the assembly after the strike. Another ‘offense’ listed is that 50 MLAs, including CPI(M) members, undertook an indefinite strike demanding assistance for drought-affected victims in Odisha.

In Chapter Four, under the sub-heading JP’s Bid to Woo the CPI(M), the IB presents open political engagements by the CPI(M) as if they were covert, terrorist acts. On September 18, 1974, CPI(M) leaders met with JP in Patna. They agreed to stand together on the shared demand for dissolving the Bihar Legislative Assembly. While the CPI(M) did not intend to be part of a consultative committee involving the Jana Sangh and other parties, the leaders expressed no objection to cooperating with the movement.

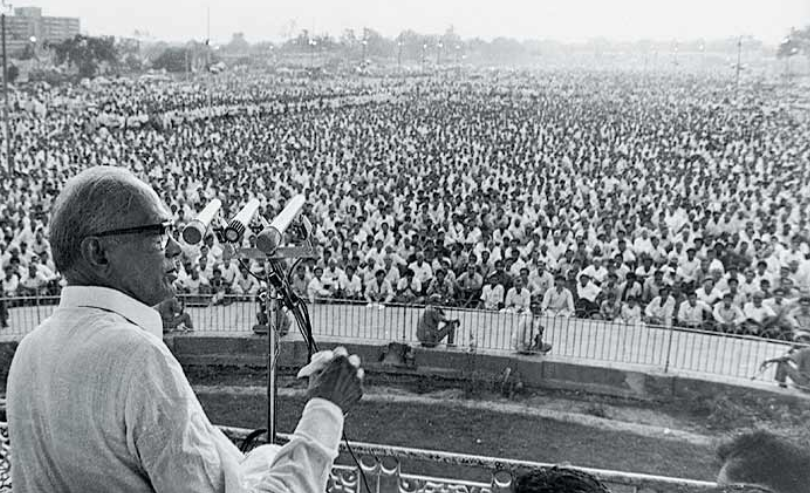

General Secretary P. Sundarayya suggested that efforts could be made to develop an all-India movement along with the struggle in Bihar. EMS Namboodiripad also noted that there was consensus with JP on many issues. Communication between JP and CPI(M) leaders continued, and when JP visited Kolkata in April 1975, CPI(M) leaders expressed their support. The IB highlights JP’s presence at a Left Front rally on June 5, 1975, as further proof of collaboration.

(Image courtesy: Outlook)

Chapter Five is dedicated entirely to the 1974 railway strike. The report asserts that the CPI(M), aligned with George Fernandes, organized the central government employees’ strike in solidarity with the railway workers. CPI(M) cadres were mobilized, and active party workers were stationed at 56 railway stations to coordinate strike preparations. The All India Loco Running Staff Association, which supports the CPI(M), is said to have played a major role in the strike—and so the report continues, stacking similar observations.

One of the more serious allegations is that the CPI(M) made clandestine efforts to instigate strikes within the police and army, allegedly forming an alliance with JP’s movement for this purpose. The IB claims that the CPI(M) was involved in promoting discontent among the police and armed forces. It cites the 1973 strike by the Local Armed Constabulary (PAC) in Uttar Pradesh, which lasted from April 21 to 26.

The report states: “The leaders of the CPI(M) considered that the mutinous behaviour of the PAC was an indication of the growing discontent among the police and other services over the current economic distress, which has been accentuated by the Government's failure to redress their long-outstanding grievances. The party seized this opportunity for extending its indoctrination and infiltration activities among the police forces in various states of the country and the armed forces…. Deshabhimani, the CPI(M) mouthpiece in Kerala, portrayed the strike as a major awakening.”

The IB further alleges that the CPI(M) sought to gain support among police forces in other states as well. It claims that campaigning was initiated among the armed police in West Bengal, and that state secretary Pramod Dasgupta had instructed party workers to help policemen raise their issues. Additionally, the report claims that both Dasgupta and Harkishan Singh Surjeet had secretly established contact with individuals in the forces through the policemen’s relatives.

(Saroj Mukherjee, Jyoti basu and Pramod Das Gupta)

However, in stark contrast to these dramatic claims, none of the weekly police-IB reports filed prior to the Emergency noted any serious internal disturbances. The July 11 report appears to have been fabricated after the Emergency was declared. It reinterprets every significant protest movement of the 1970s as a subversive act aimed at destabilizing the government.

Although prepared with clear political intent and bias, the report unintentionally offers a detailed snapshot of the protests and political movements organized by the CPI(M) during the 1970s in opposition to the Congress government’s anti-people policies.

0 comments