Backdoor NRC? Centre’s Electoral Roll Revision Sparks Fears of Mass Disenfranchisement in Bihar

Anjali Ganga

Published on Jun 29, 2025, 12:33 PM | 4 min read

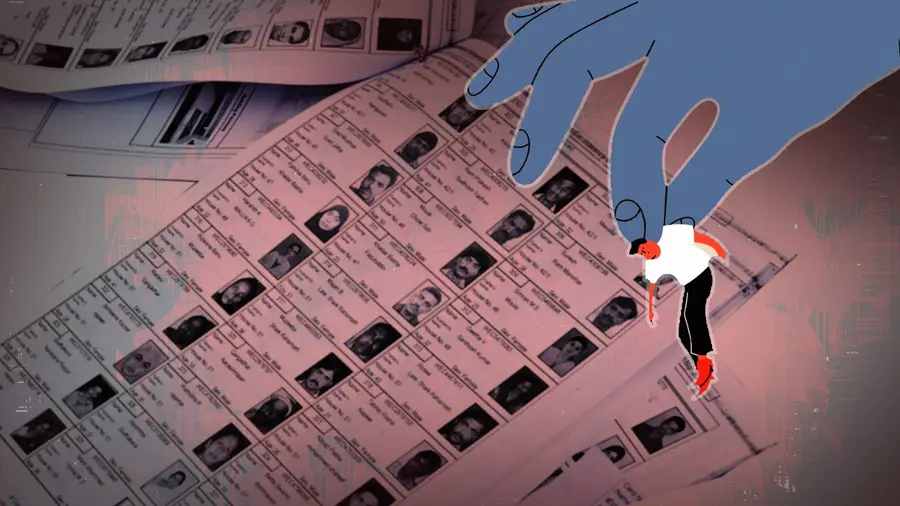

In a deeply contentious move that critics say threatens the foundations of India’s democratic process, the Election Commission of India (ECI), with full backing from the central government, has initiated a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar, demanding documentary proof of birth and parental origins from nearly 2.93 crore voters. This sweeping verification exercise, which began on June 28, 2025, has triggered a political storm, with opposition parties warning of mass disenfranchisement and comparing the process to a covert implementation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

The SIR demands that any voter whose name was not in the electoral rolls during the last such revision in 2003 must now submit valid proof of their own, and in many cases, their parents’ birth details and place of origin. The burden of proof lies entirely on the individual voter, a significant departure from past practice, raising alarm bells across civil society and the political spectrum.

Disenfranchisement by Bureaucracy

While the ECI has tried to present the move as a constitutional obligation to ensure only Indian citizens are enrolled as voters, the scale, timing, and logistical burden of the exercise suggest more insidious motives. Bihar has nearly 7.9 crore electors, out of which 4.96 crore were part of the rolls as of 2003. These voters must now simply verify their names and submit a form. But for the rest, nearly 2.93 crore people, the process is anything but simple.

Voters born before July 1, 1987 must provide documents establishing their date and place of birth. Those born between July 1, 1987 and December 2, 2004 must do the same, along with proof for one parent. For those born after December 2, 2004, documentation is required for both parents as well. In a country where official records are often inaccessible or incomplete, particularly for rural, poor, and migrant populations, this effectively turns the right to vote into a privilege reserved for the documented elite.

Nilotpal Basu of the CPI M wrote to the Chief Election Commissioner condemning the timing and methodology of the SIR. He pointed out that voters unable to receive the form from booth-l evel officers, or those who simply lack digital literacy or internet access, could find themselves arbitrarily removed from the rolls. The insistence on parental documents for young voters, or proof of residence for long-time residents, is not only unrealistic but punitive.

A Political Agenda Disguised as Verification

The opposition has accused the ruling BJP and the Election Commission of attempting to alter electoral outcomes under the pretext of administrative diligence. Opposition condemned the exercise as a Nazi-style attempt to trace ancestry and strip people of their rights, calling it a backdoor NRC. Congress echoed these concerns, warning of “wilful exclusion” of Muslim community through misuse of state machinery.

That the exercise begins in Bihar, where assembly elections are due this year, and will soon be rolled out in politically crucial states like Assam, West Bengal, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, only strengthens the suspicion. Several parties that attended the June 25 meeting with the Bihar CEO reportedly opposed the exercise, but the Election Commission went ahead regardless. The official justification, to weed out illegal foreign migrants, is being seen as a smokescreen for a much broader disenfranchisement campaign.

The ECI claims over one lakh volunteers and 1.5 lakh political party-appointed agents are assisting in the process, but these figures do little to ease fears. The process relies heavily on voters being proactive, informed, and adequately documented, which many are not. The potential for large-scale deletion of genuine voters, especially the young, the poor, and the mobile, is immense.

Elections Under Shadow

The government''s push for this revision just months ahead of the Bihar elections has raised serious questions about the neutrality of institutions tasked with safeguarding democracy. Shifting the onus of eligibility to the voter, without ensuring access to documents, legal assistance, or awareness, turns a fundamental right into an obstacle course.

More troubling is the declaration that similar revisions will be carried out in other states in 2026. This signals a centralised strategy of voter surveillance and selective exclusion, all framed as constitutional housekeeping. But the effect is unmistakable: it opens the door for politically motivated disenfranchisement.

This is not simply a case of voter list revision. It is a calculated move with far -reaching implications for India’s electoral democracy. In the name of voter purity, the very idea of universal suffrage is under assault. When the right to vote becomes dependent on ancestral paperwork, democracy ceases to be inclusive it becomes exclusionary by design.

0 comments